You may have heard of “right plant, right place” but have you heard of “right purpose”? Likely coined by Julie Weisenhorn et al. who developed a plant selection tool for the University of Minnesota Extension, this approach seeks to match plants to the conditions they evolved with rather than attempting to fit plants into conditions that may not support their long-term success. By selecting plants according to current conditions (rather than attempting to engineer different conditions), caretakers can greatly increase the chances of plant success and decrease long-term maintenance needs. Furthermore, planning for plants to die out or migrate over time is not only good design but also reflective of a broader regenerative approach to landscape gardening that allows for the caretaker to adjust to conditions as they naturally change over time. Embracing natural change and phasing plants in or out accordingly supports a more resilient and biodiverse landscape.

What is “regenerative” planting?

“Regenerative” is a definitely a buzz word these days, which means you’ll probably find multiple definitions for it across the internet. Put simply, we think of regeneration as the duty that humans have to engage the landscape in ways that extend beyond repair and support and even enhance it. The regenerative philosophy frames human kind as one of many– albeit important– components of the natural environment. In acknowledging how extensive our impact on natural processes and biodiversity can be, the regenerative philosophy suggests humans lean into our influential role to actively encourage the development of complex living systems. ReScape, a San Francisco-based regenerative landscaping workforce development organization, has distilled this philosophy down to 8 practical principles worth exploring here.

Regenerative philosophy suggests humans lean into our influential role to actively encourage the development of complex living systems.

Landscape Planting: Then and Now

Landscaping and gardening values, like most cultural values, change over time. However, some aesthetically-driven values continue to inform our perceptions of beauty and kemptness to this day. Before diving into succession and habitat gardening, let’s explore how we got here first.

Historically, gardens in the western world were a luxury enjoyed by folks who did not have to rely on their land for sustenance. Think: the wealthy nobility of France and England with their strolling gardens and highly manicured lawns. Gardens were designed as extensions of the dwelling’s architecture, continuing lines that imposed order on the landscape accordingly. Highly sculpted evergreen plants represented refinement and a triumph over chaos (nature). Sloping lawns and reflecting pools evoked ideas of infinity and power. Meanwhile, flowering plants were bred to have bigger, fuller, more frequent blooms, a practice that still takes place to this day.

Nowadays, private gardens (or yards) are a thing enjoyed by much of the first world’s middle class. If you’ve ever had your yard designed by a professional, it’s still a common practice to approach the garden as a series of outdoor “rooms” where occupants can enjoy green nature while still feeling the safety and assurance of their home. In this way, residential landscapes are still treated like an extension of the home, so it makes sense that plant and hardscape materials often reflect the owner or tenant’s stylistic preferences. Without any ingrained knowledge of local plants, the average lay person chooses plants they like with little or no practical knowledge of the conditions in which they evolved. The myriad of commercially available cultivars leaves little room to question otherwise.

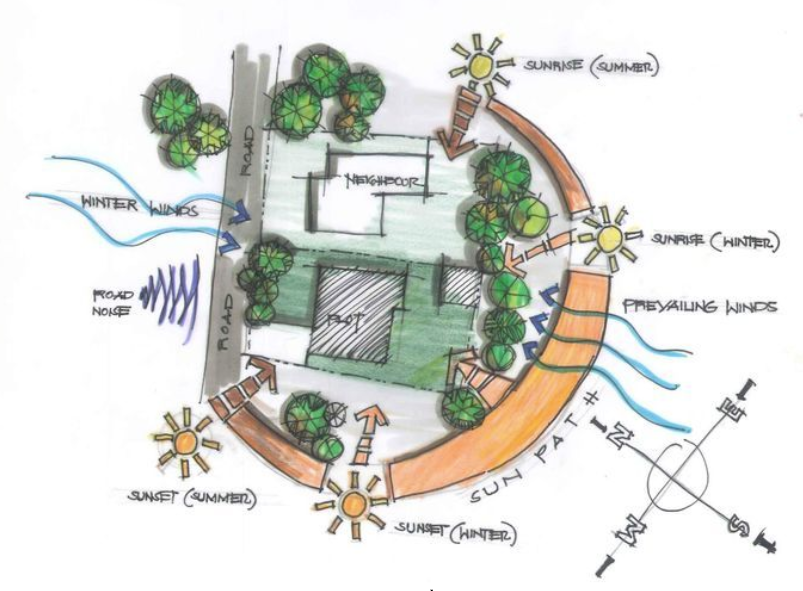

Understand Your Site

The first step to designing a planting plan is site analysis. Map your site’s existing conditions and, most importantly, how they change throughout the seasons. Most designers can’t do this for you; they will only be able to capture a single snapshot in time whereas you, the caretaker and steward, are developing an ongoing conversation with your landscape. A habitat or biodiversity-focused designer should be willing to visit the site during the winter and summer for a full picture of how the site’s exposure and micro-climates change throughout the year. This is especially important for places around the house and trees so that the changes and shade and sun angle can be directly observed rather than postulated.

The next step is to select plants that have evolved within a location’s set of conditions, rather than the other way around. Since regeneration is interested in enhancing what’s naturally occuring, responding to existing conditions with well-adapted plants (think: natives), rather than creating new conditions, is the name of the game. This idea of planting is also known as successional planting and is well-documented as a small-scale farming practice.

For landscaping, we recommend starting with CalScape.This online database of California native plants can show you what’s native to your exact location (using your address) and tell you the soil, sun, and water needs for each plant. By capturing as full of a picture of the microclimate, soils, drainage, and exposure of specific locations as possible, you can greatly improve the rate of plant success, which decreases waste and reliance on inputs over time. Stronger, well-adapted plants will make your garden more resilient to pests and drought stress over time, which will make them better able to support pollinators and withstand wildlife impacts, too.

Set Succession in Motion

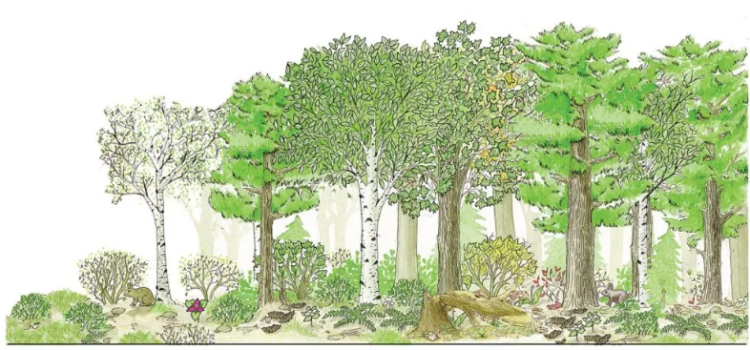

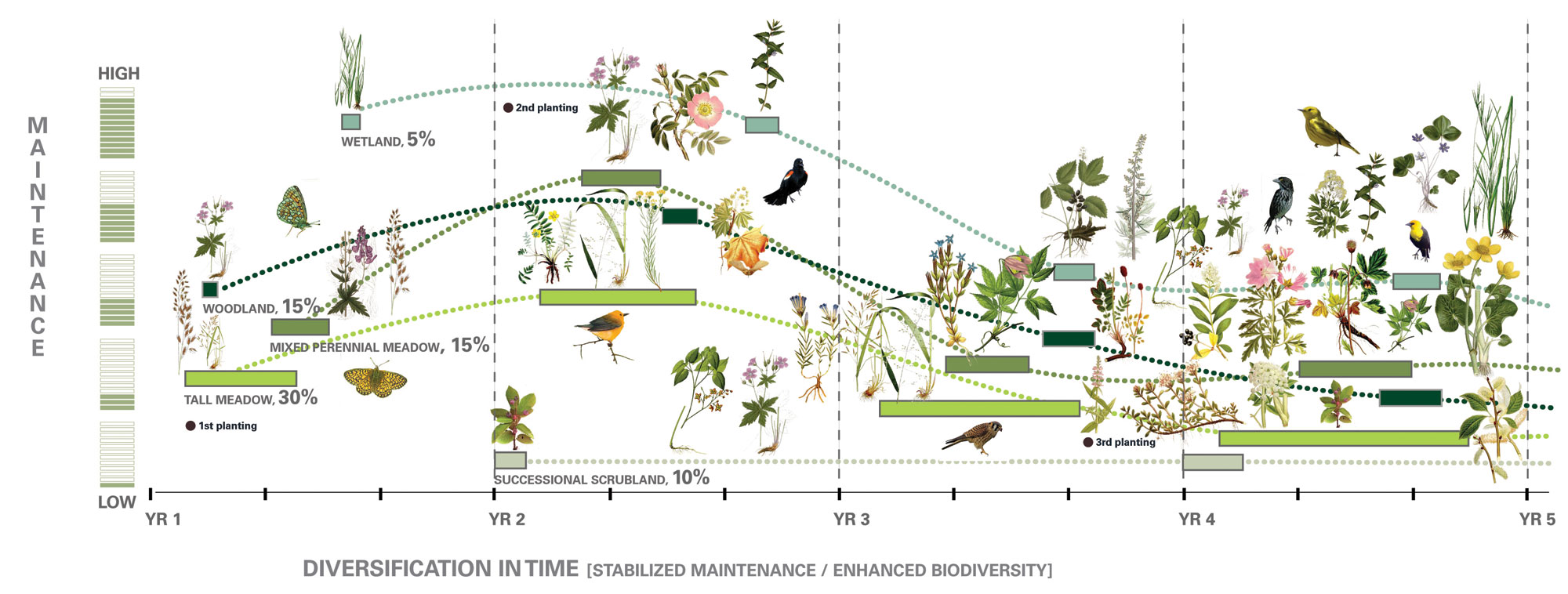

Keep in mind that adding plants (especially trees and larger shrubs) is likely to change the microclimate of one or several plant locations, so having some understanding of each plant’s influence is ideal. For example, most California native soils are nitrogen-poor, so planting nitrogen-fixing plants (i.e. most members of the pea family) outside of vegetable and herb beds will make the site less suitable over time for otherwise well-adapted native plants. Some change is inevitable, but the regenerative approach embraces those changes and asks, “What can this site support now that it previously could not?” Embracing change is an inherently adaptive mindset that can help you to anticipate the domino effects of your tinkering and recognize new opportunities as they arise in your garden. In this way you can begin to allow your garden to mimic ecological succession at the individual site scale.

One way to set the stage for this process is to phase your garden design. Depending on the site’s exposure and soils, it might be worth starting with more grasses or pioneer plants and/or larger plants and trees. This will allow the larger plants time to establish and for the pioneers to build topsoil, giving you the chance to reassess the change in soil and microclimate conditions and to select plants from the next phase that are best suited for the new conditions. This will again reduce waste in the long-run as choices are made in accordance with the direction that the site is shifting.

Another way plants influence a site is through cooperation and competition. We understand a lot about beneficial companions for food-producing plants, but we don’t know as much about how native plants help or hinder each other. However, we do know a bit about which plants are often found together in the wild, which can give us clues as to how to group them in a landscape setting. Along with growth requirements, CalScape also lists companion plants, pollinator relationships, bloom times, and more for every plant entry searched.

Embrace the “Bad” with the Good

It may be worth noting that some changes might not be for the better, in this case, an abundant, biodiverse, and resilient garden. For example, some plants may be too well adapted to a site and might overtake those around it. Contrary to popular belief, it is entirely possible for even native plants to become invasive. To be clear, any plant that spreads easily is not invasive; it’s the degree to which that plant keeps other species from growing and thereby significantly diminishing the garden’s overall diversity that determines if it’s a “weed” or not. Don’t be afraid to be your garden’s guardian; sometimes protecting the trajectory of the whole means weeding out the occasional ill-suited individual.

Be ok with knowing that your garden may take years to reach its “peak”. Make the act of observing your garden a regular practice (dare we say spiritual?). As plants grow, new pockets for later successional plants might open up while others may close. As perennial debris builds the soil, less pest management may be needed but early pioneer plants may die. Keep in mind that working in alignment with processes is an inherently time-consuming thing that pays for itself in the long-run. For this reason, developing a master plan with a variety of plants for each phase (rather than having determined plants in fixed locations) can build-in flexibility. Giving yourself the wiggle room to select species or cultivars that are aligned with your preferences as well as the direction your landscape is moving can ensure the regenerative nature of your efforts while also retaining your individual touch.